Symbolism1901

Judith I

Gustav Klimt

Curator's Eye

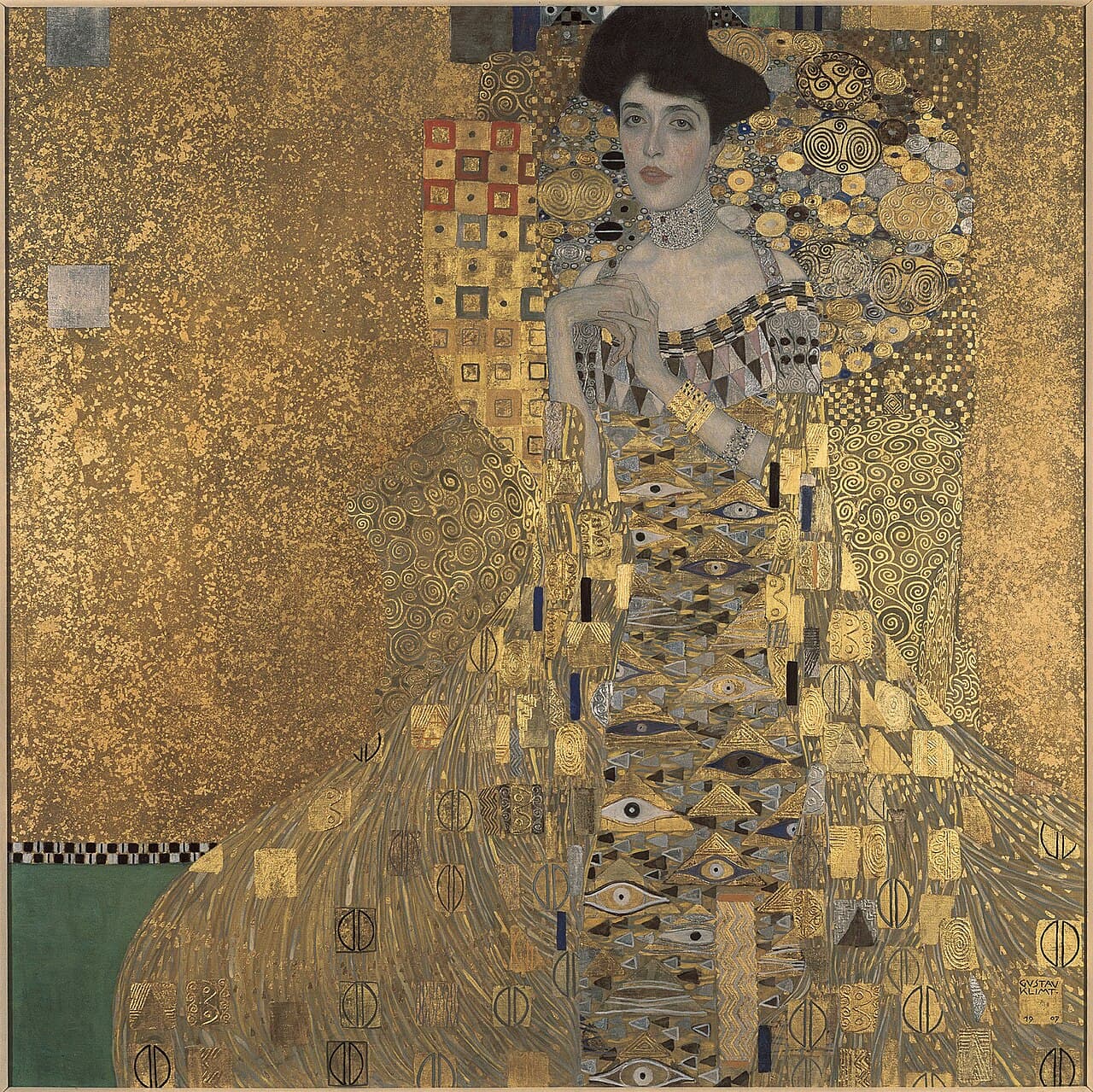

"The painting is distinguished by its revolutionary use of gold leaf and a chased metal frame that is integral to the work. Klimt captures Judith in a state of post-coital ecstasy, holding Holofernes’ head as an almost erotic accessory."

Judith I is the dazzling manifesto of Klimt’s Golden Phase, where the biblical heroine is transformed into a modern femme fatale, blending sacred eroticism with sumptuous cruelty.

Analysis

The work revisits the biblical myth of Judith, the Jewish widow who saved her city of Bethulia by seducing and then beheading the Assyrian general Holofernes. Traditionally, Judith is depicted as a figure of virtue and patriotic courage, chaste and determined. Klimt radically breaks with this reading by transforming the heroine into a sexual predator of the Viennese bourgeoisie. This semantic shift is essential: religious sacrifice fades before the drive for death and pleasure (Eros and Thanatos), central themes of Freud's Vienna at the dawn of the 20th century.

Expert analysis emphasizes that Judith is no longer a distant liberator but a woman whose desire is palpable. Her half-closed eyes and slightly parted mouth suggest a sensual pleasure linked to the murderous act. Klimt uses gold not only for its decorative value but as a sacred screen that deifies lust. The head of Holofernes, partially cut off on the right edge, is reduced to a residual presence, almost insignificant against the woman's triumphant magnetism.

In the context of the Vienna Secession, this painting marks Klimt's desire to fuse applied arts and painting. The ornamentation is not a simple filling; it structures the character's psyche. The geometric and floral patterns surrounding Judith create a Byzantine atmosphere, transforming the portrait into a modern icon. It is a celebration of female power that terrified as much as it fascinated the patriarchal society of 1901.

The treatment of the flesh, with a striking realism and an almost sickly pallor, contrasts violently with the two-dimensional abstraction of the gold. This duality between the tangible body and the immaterial background reinforces the mystical and timeless aspect of the scene. Judith belongs both to ancient myth and to the contemporary Viennese salon, making her a universal figure of masculine fascination for the "femme fatale."

Finally, the work questions the morality of violence when associated with beauty. Klimt does not judge Judith; he exalts her. He makes her the goddess of a new aesthetic religion where sin and holiness merge. It is this fundamental ambiguity, served by a goldsmith's technique, that gives Judith I its place as an absolute masterpiece of European symbolism.

Join Premium.

UnlockQuiz

What decorative material is extensively used by Klimt in this work?

Discover