Realism1855

The Painter's Studio

Gustave Courbet

Curator's Eye

"Painted in 1855, this canvas divides Courbet's world into two categories: on the left, those who live off death and exploitation; on the right, friends and intellectuals. At the center, the artist asserts himself as the sovereign mediator."

A true manifesto of Realism, this monumental work by Courbet is defined as a "Real Allegory." The artist depicts his own social, political, and artistic life in a format traditionally reserved for grand history painting.

Analysis

The Painter's Studio marks a radical turning point in Western art history. Subtitled "A real allegory summing up seven years of my artistic and moral life," Courbet merges two previously contradictory concepts: allegory, the realm of abstraction, and realism, the realm of raw truth. This nearly six-meter-wide canvas rejects Academic codes to establish the figure of the artist as the center of gravity of the modern world. Courbet does not paint a genre scene, but a philosophical assessment of his existence and commitments.

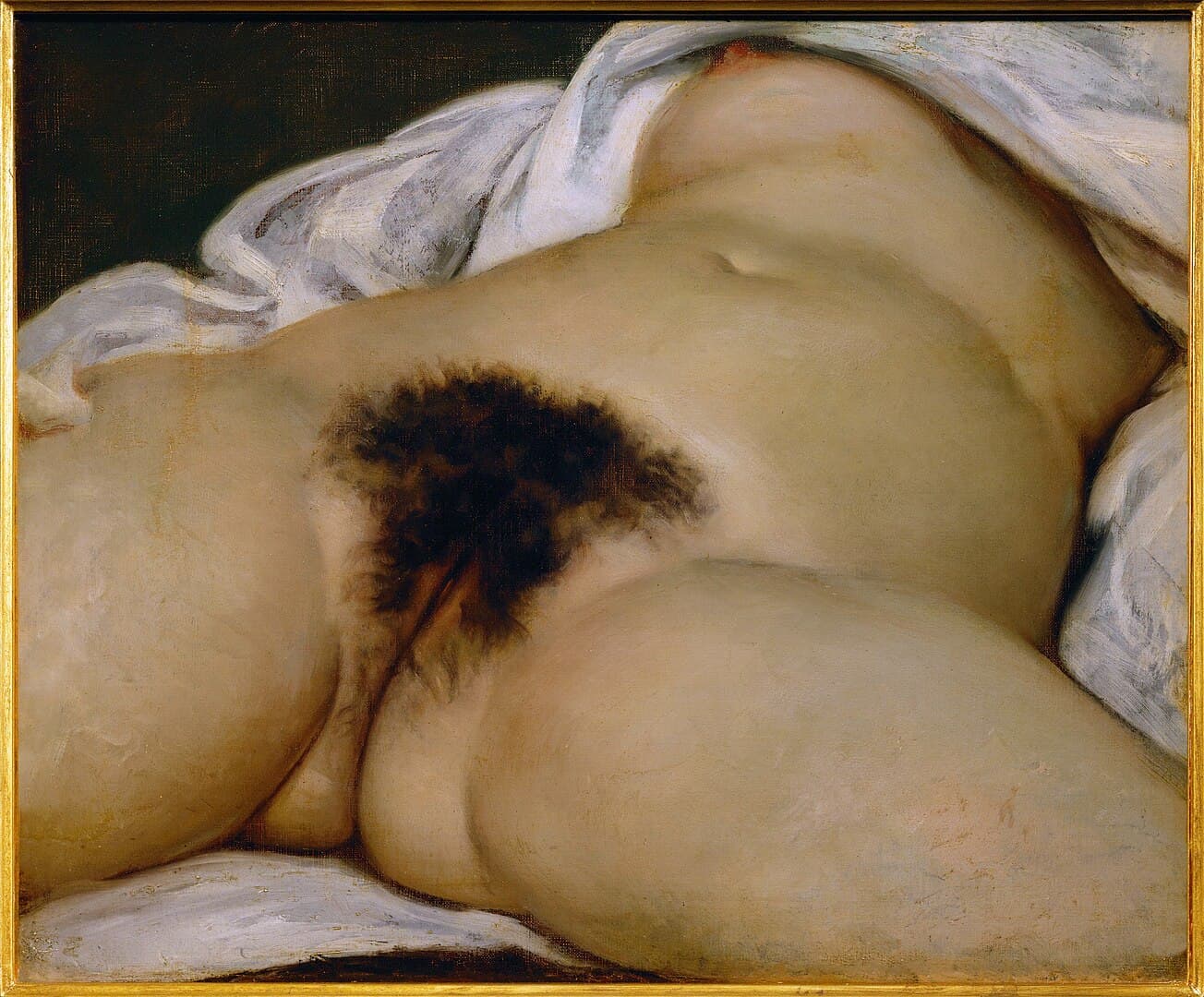

The painting functions as a theater of the world. On the left is "the other world," that of trivial life, misery, exploited wealth, and representative social types (the priest, the poacher, the merchant). Courbet treats them with an almost religious gravity, highlighting the inertia and melancholy of this social class. In contrast, the right side gathers the "shareholders," the intellectual and artistic elite supporting Courbet, including Baudelaire, Proudhon, and his patron Bruyas. Between these two spheres, the artist paints, turning his back on the nude model, a symbol of unadorned Truth.

Courbet's pictorial execution demonstrates incredible material power. Using a palette knife to crush the matter, he gives the paint an earthy, dense texture. The dark, bituminous backgrounds recall Spanish and Dutch masters, but the light hitting the center of the canvas is resolutely modern. This paint density embodies Courbet's will to make art "palpable." For him, painting must not just represent; it must physically exist with the force of nature itself.

Finally, the work is an act of political defiance. Rejected from the 1855 Universal Exhibition, it became the heart of the "Pavilion of Realism" that Courbet built at his own expense. This was the first time an artist organized a private exhibition against the official institution. The Studio is not just an image; it is a monument to creative independence. It foreshadows the autonomy of modern art and the birth of the avant-garde, where the artist becomes the sole judge of their value and message.

Join Premium.

UnlockQuiz

What does the nude woman standing behind the painter represent?

Discover