Fauvism1910

Dance

Henri Matisse

Curator's Eye

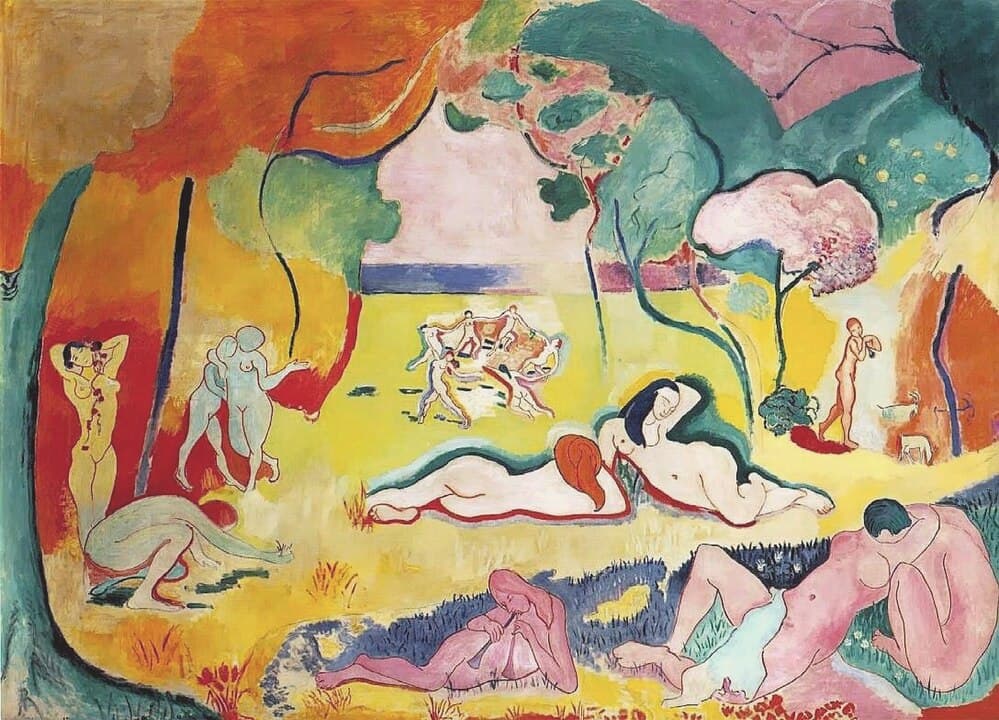

"The Dionysian red of the bodies stands out against the azure sky and the green hill. Note the broken circle at the bottom left: this void invites the viewer to join the dance and complete the circle of humanity."

An icon of modernity, this monumental canvas embodies the apotheosis of Fauvism. Through three primary colors and five bodies in motion, Matisse captures the primitive essence of life, joy, and universal rhythm.

Analysis

The stylistic analysis of *The Dance* reveals Matisse's desire to simplify expression to its archetypal core. Commissioned by Russian collector Sergei Shchukin for his Moscow palace, the work was born in a context of radical rupture from academic naturalism. Matisse uses the "Fauve" style not to describe an optical reality, but to translate pure emotion. The choice of three colors—red for human flesh, blue for the cosmos, and green for the earth—reduces the world to its elemental components. This economy of means is a quest for the absolute where color becomes the very structure of space.

The mythological and historical context draws from the sources of Antiquity and Primitivism. Matisse was inspired by the village dances of Collioure but transcended them to evoke ancient bacchanals and the Golden Age. There is a direct resonance here with the myth of Dionysus, the god of intoxication and collective ecstasy. The bodies have no distinctive features; they are vital forces, generic entities celebrating the primordial link between man and nature. The psychology of the work is one of self-abandonment: dancers lose their individuality in the rhythm of the group.

Matisse's technique relies on an extraordinarily supple line, where the contour seems dictated by the very movement of the bodies. The paint is applied in large flat areas (aplats), without modeling or chiaroscuro, suppressing all traditional depth. This radical flatness shocked contemporaries in 1910, but it liberated the canvas from being a window onto the world, turning it into an autonomous decorative surface. The artist seeks to reach the "essential" by eliminating superfluous details, a process that prefigures abstraction.

Finally, the work must be understood as a challenge to verticality. Matisse destabilizes the horizon: the green of the curved hill seems to be a portion of a rotating terrestrial globe. This sensation of perpetual motion is reinforced by the vibratory intensity of the complementary colors. The red appears to advance toward the viewer while the blue recedes, creating a spatial respiration that gives the canvas its monumentality. It is a visual meditation on brotherhood and kinetic energy as the creative principle of the universe.

Join Premium.

UnlockQuiz

What do the three dominant colors (blue, green, red) in this work represent?

Discover