The Glory of the Heroic Body: Anatomy as Sacred Science

If perspective allowed for the construction of the theater of the world, a far more perilous and fascinating task remained for Renaissance artists: to breathe life back into the lead actor, Man. Throughout the Middle Ages, the human body was viewed with deep doctrinal mistrust. It was considered the prison of the soul, the seat of original sin, an unworthy carnal envelope concealed beneath heavy, flat, and rigid drapery. Medieval artists did not seek to understand the internal mechanics of muscle or the structure of the skeleton, for the flesh was deemed ephemeral and irrelevant compared to the eternal spirit. Bodies were thus often ethereal, symbolically elongated, devoid of weight and volume, floating in a gravity-less space where only spiritual hierarchy dictated the size of beings.

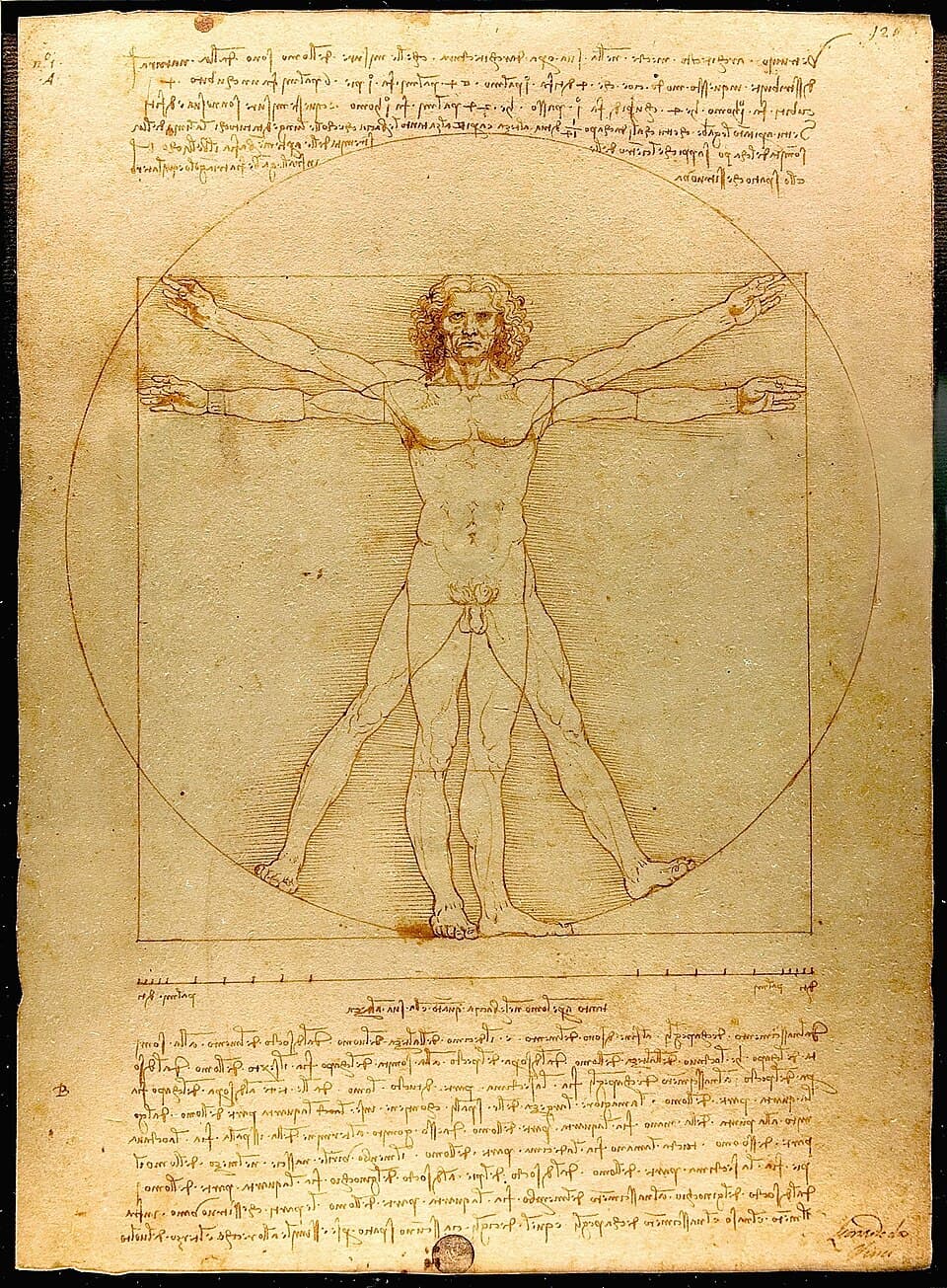

The Renaissance operates a total anthropocentric reversal: the human body becomes the ultimate masterpiece of divine creation, a microcosm reflecting the harmony of the universe. It is no longer hidden, but exalted. Yet, to exalt it with absolute truth, one must first dare to look at it without a filter, to dissect it, and to pierce its deepest secrets.

This quest for truth pushed the greatest geniuses to clandestinely cross the doors of morgues and hospitals. Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, at the risk of their reputations and sometimes defying religious bans on the manipulation of corpses, practiced human dissection almost obsessionally. Leonardo, in particular, filled his notebooks with thousands of sketches of surgical precision, studying the exact function of each tendon, the curvature of each vertebra, and the complex mechanics of heart valves. He did not merely paint a surface of skin; he painted the dynamic tension of the muscle beneath. This approach radically changed the nature of the image: the painted character now possessed physical density, a real bone structure, and a true gravitational force.

Leonardo da Vinci's Vitruvian Man: The absolute synthesis between mathematical geometry (circle and square) and perfect anatomical harmony.

Michelangelo, for his part, pushed this logic toward a form of corporeal mysticism. For him, the male body was the exclusive vehicle for spiritual emotion and the soul's struggle. Each twist of the torso (the famous *contrapposto*), each protrusion of a tricep or tendon expresses a state of inner tension. His 'David,' sculpted from a giant and defective block of marble, marks a raw break from previous representations. It is no longer Donatello's frail adolescent, but a Herculean athlete at rest, whose nervous tension is nonetheless electrifying: observe the bulging veins on the back of his right hand, the furrowed brow, and the powerful contraction of his thighs. Michelangelo invented 'terribilità': that contained power seemingly on the verge of exploding. The body is no longer a mere statue; it is a psychological and emotional engine.

Michelangelo's David: Observe the precision of the muscles and veins. The sculpture does not merely imitate form; it captures the nervous tension of a body on alert.

This anatomical revolution did not stop at the perfection of physical form; it integrated deep psychology. Artists began to paint what Leonardo called the 'motions of the mind' (i moti del mente) through subtle facial expressions and complex hand gestures. In his masterpiece of human communication, 'The Last Supper,' each apostle reacts to the news of betrayal with a specific anatomical posture, dictated by his own temperament. Art becomes a clinical and poetic study of humanity in crisis. The artistic nude was also rediscovered, no longer as a representation of original shame, but as a celebration of ideal beauty inherited from Greek canons. Flesh is no longer the seat of sin; it is the mirror of mathematical perfection and the harmony of the entire universe.

Leonardo da Vinci's Last Supper: A catalog of human emotions. Look at how the anatomy of the hands and necks translates the dread, anger, or doubt of each apostle.

What spirit is so empty and blind that it cannot grasp the fact that the foot is more noble than the shoe, and skin more beautiful than the garment with which it is clothed? The body is the mirror of the divine soul.

Yet, this total mastery of form, bone, and muscle would lead artists to a new question: perfection can seem frozen, almost too brutal if it is too sharp. After taming space (perspective) and volume (anatomy), one last element remained, the most elusive of all, to be conquered: atmosphere and the passage of time. How does one paint the air circulating between bodies? How to capture the mystery of a gaze that seems to elude us? This final challenge would be met by Leonardo da Vinci, who invented the technique that would bind everything in a mist of genius: Sfumato. This is the subject of our next stop at the heart of the mystery of creation.